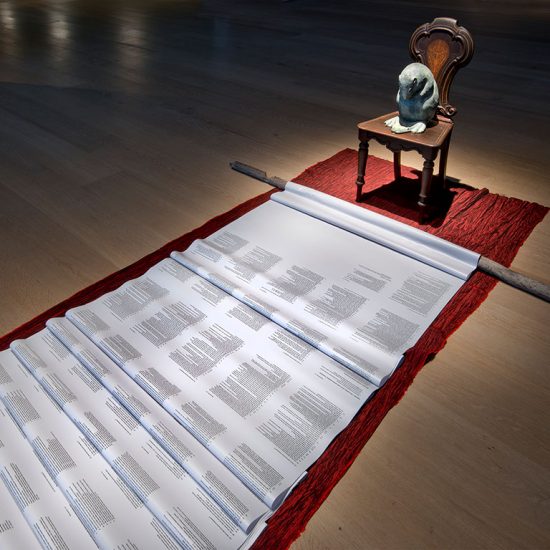

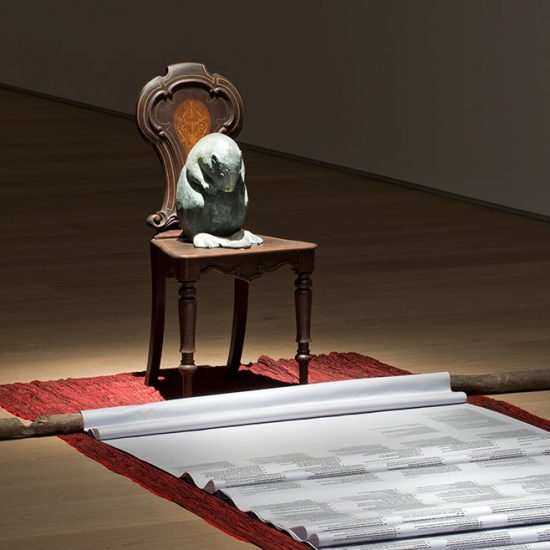

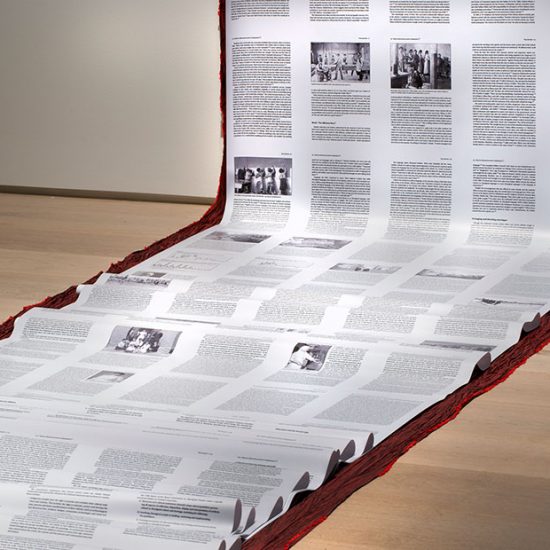

Le rêve aux loups (2017 | Esker Foundation, Calgary, Alberta)

SEPTEMBER 16 – DECEMBER 22, 2017

Curator: Jennifer Rudder

From the Esker Foundation:

Mary Anne Barkhouse’s artistic practice is deeply engaged with environmental and Indigenous issues, and evokes the influence of empire on the many human and animal inhabitants of the land we now call Canada. The works in Le rêve aux loups (The Dream of Wolves) reflect on the mistaken colonial understanding of land and nature as commodities for human exploitation, rather than as a shared resource and an ecosystem with its own intrinsic value.

Barkhouse’s bi-coastal heritage taught her the individual and communal importance of stewardship of the land. She spent alternate summers fishing on the Pacific Ocean with her Kwakiutl grandfather, Fred Cook – a fisherman, logger, and carpenter – and looking after the animals close to the Atlantic Ocean with her German settler grandfather, Alfred Barkhouse – a farmer in Nova Scotia. In her work, the artist employs a visual iconography of animals – including the owl, wolf, bat, and coyote – both as symbols of persistence, resilience, and regeneration, and as a way to address her commitment to the active Kwakiutl and farming practices of conservation and sustainability.

For this exhibition, Barkhouse has expanded the scope of her practice in the creation of three new works that respond to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and the horrific legacy of the Residential School system. Situated in two rooms, Aerie positions baby birds of prey inside of what Barkhouse terms “child containment units”: a Victorian wicker pram and an iron crib. These items of colonial furniture seemingly nurture and offer the birds protection, however, in reality they inflict a betrayal as tools of confinement and control. In this dream-like apparition, the porcelain faces of the baby owl, vulture, and eagle stare up at us. These young birds will mature into strong and powerful creatures, and with the traditional mythological figures of Thunderbird and Raven tucked in beside them, there is the possibility of spiritual hope for the fledglings.

Elsewhere, seven species of the Boreal forest cohabit in an ideal vision of adaptation and survival in the installation, Empire. Despite their differences, they live comfortably together in a large, contiguous habitat. In pairs and alliances they hunt, share food, and warn each other of danger in biological equilibrium; a concept we humans have largely lost as the contestations over land and the renegotiation of territory continues in Canada. With Treaties in dispute and continued human expansion into farmland and bush, the ability of Indigenous people, animals, and even forests to adapt and adjust is under pressure. Amid tension along boundaries and borders, Empire, along with the other sculptural installations in the exhibition, reminds us of the need for coexistence and resistance against isolation, fragmentation, and alienation.

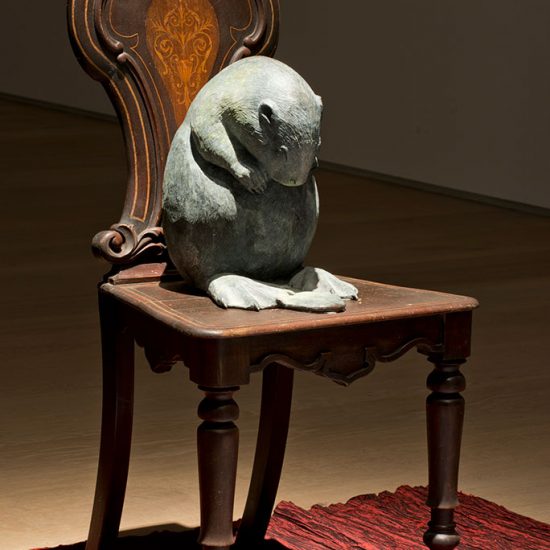

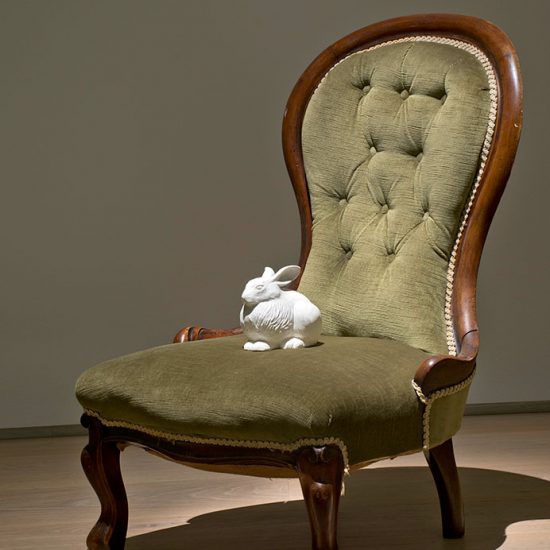

Barkhouse’s polished artworks possess a quiet beauty as they remark on contentious struggles. She takes inspiration for some of her sculptures from the still lifes of seventeenth-century Dutch painter Melchior d’Hondecoeter, known for his depictions of woodland animals or birds, both alive and dead, in lush, woodland settings – works exemplary of the era’s decorative and aesthetically appealing renderings of aristocratic excess and celebration of humanity’s dominance over nature. The Baroque influence of d’Hondecoeter’s era and the historic conflict between the natural world and the “civilized” world drives Barkhouse’s work. “Juxtaposing the wild with the wildly opulent,”[1] her dignified sculptures of birds and mammals are staged with elements of the interiors of French and English colonial luxury: the furniture of wealthy colonizers at the time of contact.

Barkhouse’s installations suggest a collision between the historic home, a theatre set, and a Natural History Museum. Owls, beavers, and foxes perch on polished English dining tables made from Canadian beech with the carved talons of a bird of prey, or they stretch out on French, lichen-green velvet chaise longues. As we move between rooms (or galleries) the luxurious mise en scène of her sculptures is embellished with gilded French side tables, cast glass goblets of hibernating bats, and family dynasty portraits of wolves presented in ornate baroque picture frames. In a subversion of the narrative of land theft and politics, the animals have taken over the parlour, begging the questions: “Who owns this land?” and “Who is the intruder?”

– Jennifer Rudder, Guest Curator.

[1] Mary Anne Barkhouse in Boreal Baroque, Catalogue. Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa, 2007.

More information on the Esker Foundation website.

(IMAGES: Courtesy of the Esker Foundation | Photographer John Dean)

View other included works, also shown in How to breathe forever at the Ontario College of Art & Design University’s (OCADU) Onsite Gallery, here. View the exhibition at the Koffler Gallery in Toronto here.

Date

December 27, 2019

Category

Exhibitions